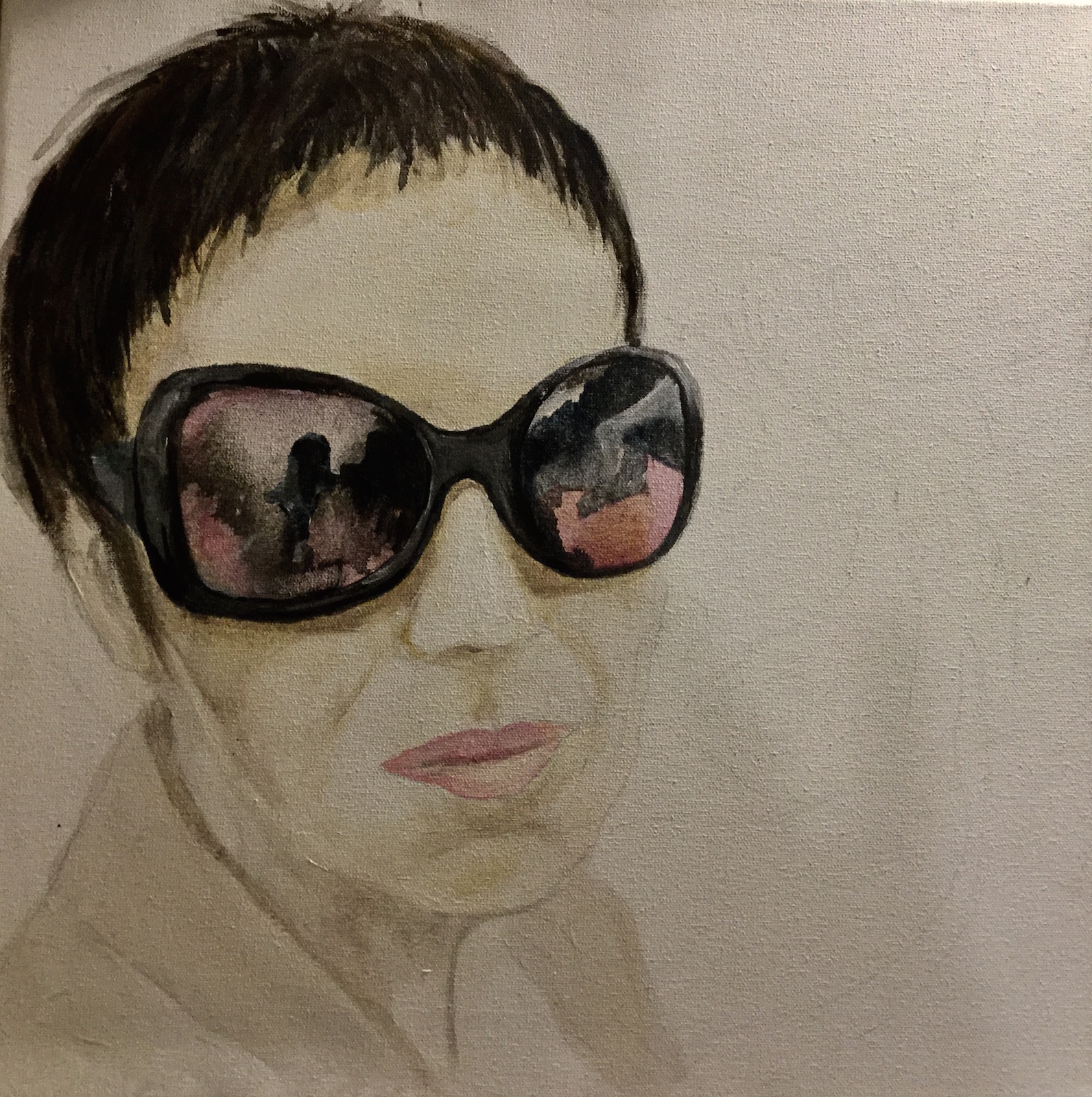

A sketch on Beata Zuba’s painting

Agata Wąsowska-Pawlik

Director of International Cultural Centre in Kraków

Beata Zuba, a painter, a women with a unique, nearly seismographic sensitivity. Her artistic activities originate from a deeply held need to express her own feelings inspired not only by ideas or places (a trip to Lisbon, for example) but, often, by a difficult history we’d rather not remember. Beata Zuba wants to encourage us to reflect on our own sensitivity, on our relation to “the Other”. In one of her self-portraits, standing at a window with her back to us – like figures in Caspar David Friedrich’s or Salvador Dali’s paintings – she makes us “watch” with her, “see” beyond ourselves, take the path of knowledge.

One of her most interesting cycles is “There” – inspired by a visit to a dilapidated, former Jewish mental hospital, “Zofiówka”, in Otwock. Most of its patients were killed during the liquidation of the Otwock ghetto in August 1942. Afterwards, it was turned into a “Lebensborn” operation centre aimed to “supply” the Third Reich with new German citizens. Beata paints open windows, often without panes, stairs leading to nowhere, abandoned and decrepit spaces. She’s one of the artists who process in their art the inexplicable experience of Holocaust. Beata Zuba, however, sets a trap for us. She creates beautiful refined colour compositions with rough textures. Her paintings seduce us with greys, a spot of paint with visible brushstrokes. At the same time, through motifs leading to “nowhere” Beata talks about the tragedy of people doubly punished, for being Jewish and for being ill. The painter asks us to: look deeper, become interested, show care. Have we really learnt a lesson from history and do we now approach ill people with sensitivity? Despite their beauty, those painting were not made to please our eyes. We must place them deep in our souls and let them do their work.

Among Beata Zuba’s paintings we can also find some works of a lighter kind. One of my favourites is a still life with a skillet, an egg and a bowl leaning up against the wall warmly painted with greys, browns and a touch of white and yellow, in flat brushstrokes. It brings to mind Dutch vanitas still lifes with their idea of transience, the passage of time and vanity of life. Even though Beata, a Francophile, will probably classify the painting as nature morte, I’d rather view it as English still life. Quiet life, balance, sensitivity to the beauty of the moment, these are also most important things. Beata Zuba is a mature artist, in her case a lack of youthful idealism is an added value.

Stairs recur in many of her paintings. Usually painted from the bottom, from a worm’s-eye view, leading up, often to “nowhere”, to some invisible destination. Stairs mean effort, necessity to climb, tiredness or, at least, gasping for breath. Beata Zuba, let me say it once again, tells us: you have to make an effort, knowledge doesn’t come easy, but the reward for the toil is awareness, emotions, skills. Art is effort. That what we merely like is not capable of changing us. Development, working on ourselves, transformation are the meaning of life.

Finally, a few words about portraits which form a large group among her paintings. Portraits of her family, relatives, friends, frequently shown wearing glasses. The glasses cover the eyes, not letting us look into the souls of the subjects. The painter watches her reflection in the eyeglass lenses, so, in my opinion, these are double portraits: of an artist and of a person – in a tender conversation. And that’s how I can describe her painting: a tender conversation. I’m grateful that Beata Zuba has invited me to one.

Kraków, January 1st, 2018